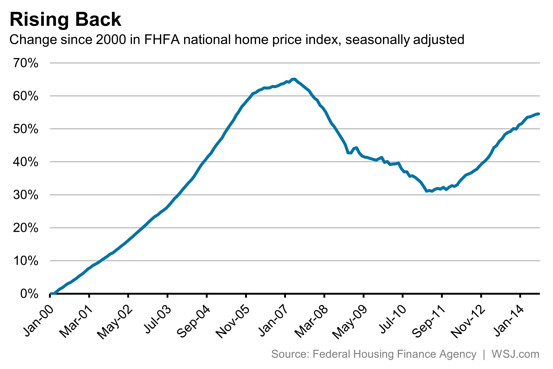

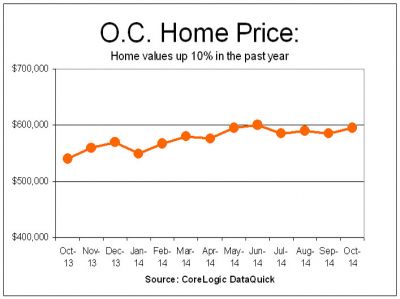

The housing bubble brought bidding wars — wars over $500,000 properties that ultimately sold for $600,000, wars over under-listed condos that drew dozens of would-be buyers, wars over starter homes that a few years earlier would have fetched a fraction of the price. This manic bidding was, in effect, a sign of the bubble, as well as a factor that helped inflate it.

The housing bubble brought bidding wars — wars over $500,000 properties that ultimately sold for $600,000, wars over under-listed condos that drew dozens of would-be buyers, wars over starter homes that a few years earlier would have fetched a fraction of the price. This manic bidding was, in effect, a sign of the bubble, as well as a factor that helped inflate it.

But a curious thing has happened since the housing market has returned to something more rational: The bidding wars haven’t gone away.

A practice that was rare in the 1980s and 1990s now seems here to stay in markets like Washington, D.C., a permanent gift of the housing bubble (if you want to look at it that way). Lu Han and William Strange, economists at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, have concluded as much after looking at data from the National Association of Realtors dating back to the 1980s.

They find, in research published in the journal Real Estate Economics, that only around 3 to 4 percent of homes on the market across the country were selling in bidding wars for years prior to the bubble. Then at the bubble’s peak, nearly 30 percent of homes in metropolitan D.C. were selling this way, the highest share of any metro Han and Strange studied. The same was true of about 22 percent of home sales in Baltimore and Norfolk, 23 percent in Las Vegas and 26 percent in Los Angeles.

Since the housing collapse, these crazy numbers have declined, but not back to their earlier levels. As prices have fallen and the number of home sales has, too, bidding wars haven’t disappeared apace. That means that we’re probably seeing not just a lingering effect of the housing bubble, or even a pure product of high housing demand, but a new strategy for selling homes that was embraced during the bubble.

“The persistence of this suggests that people have decided that this is a good way to think about selling these kinds of goods,” Strange says, “selling housing in a more auction-like way.”

If a list price once meant the seller’s ceiling, for many homes it’s now the buyer’s floor — the number with which the auction can begin. Part of what’s going on here, Strange says, isn’t just that the small supply of homes for sale continues to push up their price in certain markets like D.C. (bidding wars still made up about 12 percent of sales here as of 2010). Real estate agents are also strategically listing homes below their value to createbidding wars.

“One way to see all of this is that housing is this incredibly important good, it’s easily the most important asset in a typical household’s portfolio. As a share of total wealth, housing is huge,” Strange says. “And yet, the way houses are getting marketed, very broadly speaking nowadays, is an awful lot like it was 50 years ago.”

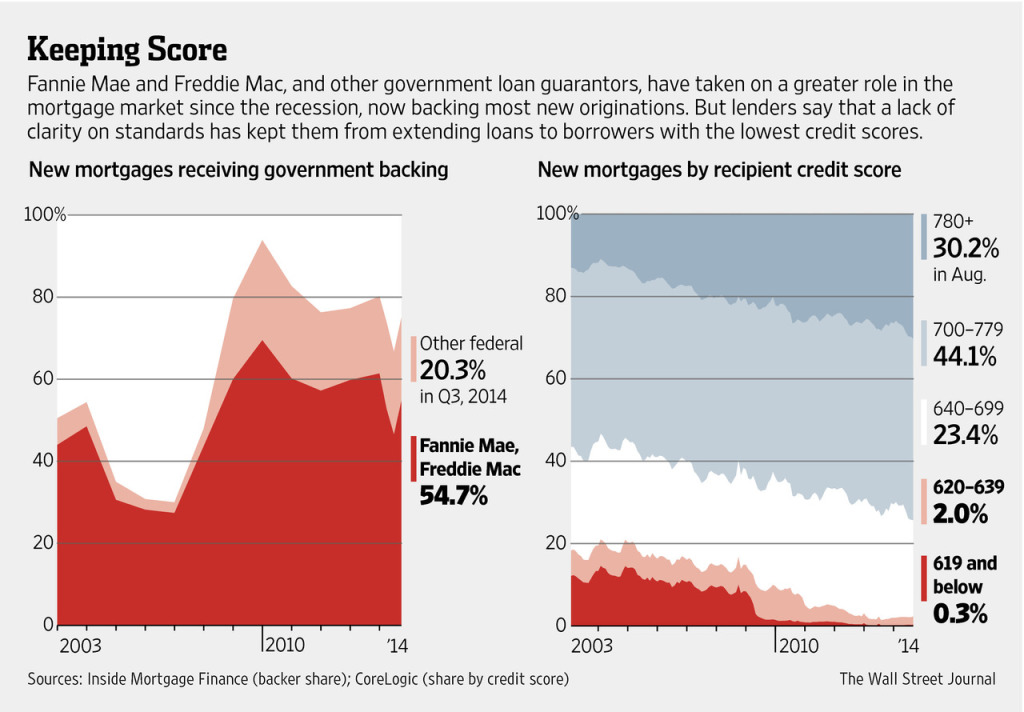

If you’re a buyer or a seller, you sign a contract with a real-estate agent who understands what’s going on a lot better than you do. They negotiate on your behalf and split a commission, typically about 6 percent. The way information is traded — through home visits, negotiations and market comparisons — is more or less how it’s been done for decades. For most of this time, buyers would set an aspirational price, then negotiate down from there.

“With the rise of bidding wars, we shouldn’t think that the housing market — like other markets — is just going to keep doing things in the old traditional ways forever and ever,” Strange says. “There are going to be changes.”

Australians have long bought housing like Americans buy high-end art — at auction. So what’s to say more of us won’t buy housing like that in the U.S. too?

Whether or not that tactic is actually making sellers more money — it’s hard to know in this data — some agents must believe that it does. The result for the rest of us is that an opaque market becomes even more so. You may think a $300,000 home is in your budget, only to find that the sellers never intended to accept that little anyway. You may struggle to gauge the difference between a $400,000 home and a $500,000 one because you can’t tell which one — or both? — is intentionally under-listed.

Now add to the confusion of buying a home the sometimes irrational emotional of an auction. Other research suggests, for instance, that some people online are willing to pay more at auction than they will for the exact same item on a one-click purchase. It’s hard to believe similar behavior doesn’t seep into housing auctions as well.

“People are making these million-dollar trades,” Strange says of homebuyers. “But we really don’t know that much about the housing market, where it’s going, what demand and supply are. It’s an amateur market where people are making these huge, huge decisions.”

At the very least, here is a free piece of information for your frantic search if you’re buying a first home to haven’t bought a new one in 15 years: Bidding wars are now a thing.

[gravityform id=”13″ title=”true” description=”true”]

Halloween Fair and Haunted House

Halloween Fair and Haunted House Anaheim Fall Festival & Halloween Parade

Anaheim Fall Festival & Halloween Parade Halloween Treat-or-Treating at Anaheim Town Square

Halloween Treat-or-Treating at Anaheim Town Square Kidz Block Party

Kidz Block Party

Pacific Symphony ‘Sherlock Holmes Halloween’

Pacific Symphony ‘Sherlock Holmes Halloween’

City of Cypress Halloween Carnival

City of Cypress Halloween Carnival Halloween Kids Boo Cruise

Halloween Kids Boo Cruise